Symphony No. 1 in C♯ Minor, Op. 1 — In The Eternal Day

by Arashk Azizi

“In The Eternal Day” is Arashk Azizi’s first official release, a large‑scale programmatic symphony inspired by The Conference of the Birds by the 13th‑century Persian poet Attar of Nishapur. This monumental allegorical work, originally composed in nearly 4,500 lines of verse, is here transformed into 1,222 bars of orchestral music.

Reading the name of the symphony's movements back to back, creates a short poetic phrase:

A Familiar Song,

Sings Into My Ear,

In The Eternal Day,

Reduced By Flames To Ashes,

The Phoenix Once Again Shall Rise.

In Attar’s mystical narrative, a gathering of birds sets out on a spiritual quest to find the Simorgh, their legendary king. They journey through symbolic valleys, each representing a stage of inner transformation. Many falter along the way, and only thirty reach the end. There they discover not an external monarch, but their own reflection: in becoming united through the journey, they have themselves become the Simorgh. In Persian, Simorgh literally means “thirty birds.”

In the Eternal Day Symphony

Azizi’s symphony follows this spiritual and psychological arc, cast in five interconnected movements. Its architecture recalls the narrative symphonism of Beethoven’s Sixth or Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, yet incorporates the dramatic role of a piano soloist, functioning as storyteller and at times assuming the prominence of a concerto part. Throughout the work, an idée fixe — the Simorgh theme — recurs in various guises, unifying the journey from first awakening to ultimate transformation.

Symbolism and Structure

The symphony is at once a narrative journey and a meditation on rebirth. The arc mirrors both the mystical stages of Attar’s Conference of the Birds and the myth of the Phoenix: aspiration, trial, collapse, death, and resurrection. The collapse at the end of the third movement parallels the birds’ devastating realisation at the journey’s end — that the Simorgh they sought is themselves — while the rebirth of the Phoenix in the fifth movement embodies the unity, self‑recognition, and spiritual awakening at the heart of the poem.

Though firmly symphonic in conception, In The Eternal Day bears the dual nature of a concerto‑symphony, with the piano as both protagonist and narrator. Its continuous interplay between orchestral mass and intimate solo voice reflects the individual within the collective — a metaphor for the journey of the thirty birds to the one Simorgh.

The Movements

A Familiar Song (Andante)

The hero hears a call — a familiar sign that stirs the longing for a greater truth. Two contrasting ideas appear: a lullaby‑like theme suggesting dormant innocence, and a march‑like figure heralding movement. In the final pages, the Phoenix theme emerges for the first time, igniting the quest.Sings Into My Ear (Adagio)

The journey toward knowledge begins. A lyrical woodwind theme (“Knowing”) alternates with a bracing march for brass, symbolizing the hardships of learning. The piano intervenes as narrator, guiding the hero through alternating moments of struggle and insight.In The Eternal Day (Moderato)

In sonata form, this movement portrays the vastness of the road ahead. A tragic first subject opposes a vigorous Simorgh‑like second. A long modulatory bridge — traversing all thirteen keys of the circle of fifths over a woodwind fugato — evokes the complexity of the quest. The movement builds toward a grand, expected triumph of the Simorgh motif, but the French horns deliver a startlingly wrong‑toned chord. The epic finale collapses in harsh dissonance — a musical shock mirroring the moment in Attar’s tale when the surviving birds realise they have not found the Simorgh as imagined.Reduced by Flames to Ashes (Allegro)

The fire is unleashed. Its relentless rhythmic figure consumes the hero’s theme, initiating a violent struggle between the Simorgh motif and the flames. The hero is defeated; the Simorgh motif appears broken, intertwined with the rhythm of death. This is the stage of annihilation — the burning away of the old self.The Phoenix Once Again Shall Rise (Allegro moderato)

From the darkness of ashes, the Phoenix stirs. Early attempts at flight falter; themes from earlier movements return, altered and unstable. The piano leads the music back toward the home key, recalling the Simorgh‑like theme of the third movement and finally asserting the full, unbroken Simorgh motif. The orchestra joins in an exultant, harmonically anchored climax — the hero and the Simorgh revealed as one, the transformation complete.

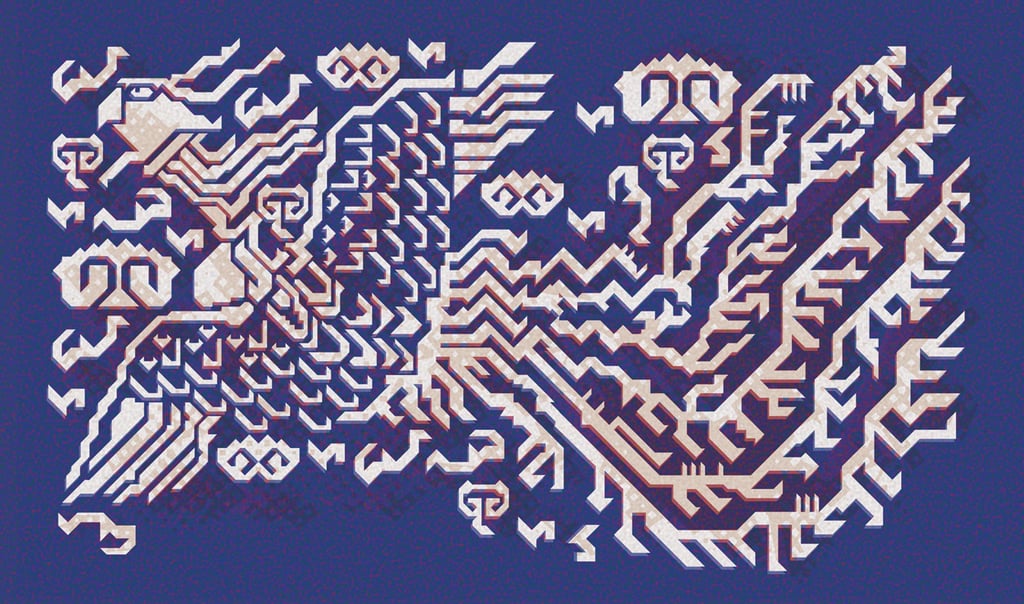

the cover album of the symphony has been created by Rahman Radmard, based on image of phoenix, late 13th century. Excevated at Takht-i Sulaiman, Iran.

The symphony’s architecture mirrors the inner journey at the heart of Attar’s Conference of the Birds. Each movement reflects a stage of transformation — from the first awakening, through trials, despair, and symbolic death, to the final revelation of self‑realisation. Just as Attar’s thirty birds discover the Simorgh within themselves, the hero of In The Eternal Day comes to embody the Phoenix, rising renewed from the ashes of the journey. Understanding the profound allegory of Attar’s poem is essential to fully appreciating the symbolic and emotional depth of this symphony.

About The Conference of the Birds

by Attar of Nishapur (12th–13th century)

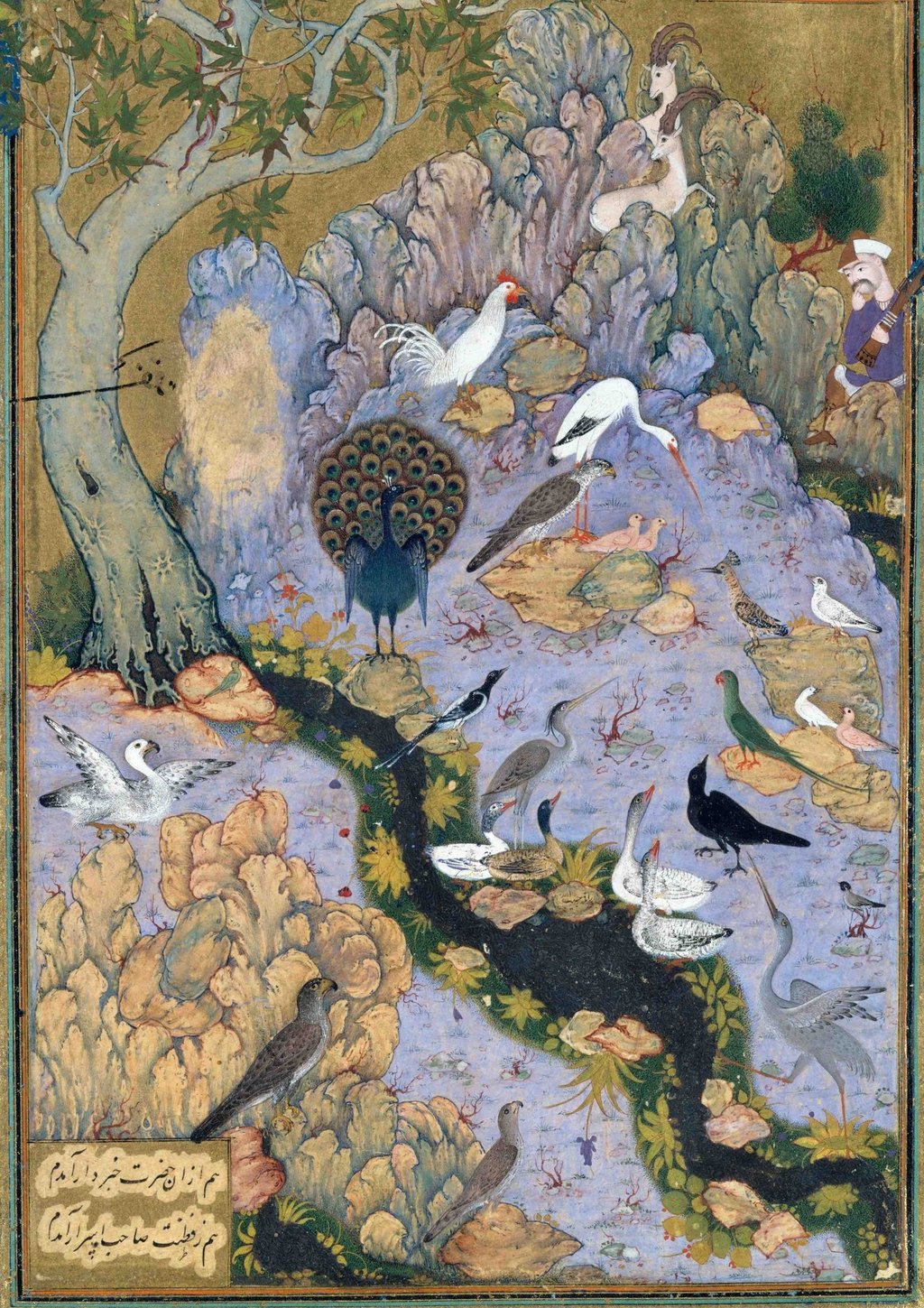

The Conference of the Birds (Manṭiq al‑Ṭayr, literally “The Speech of the Birds”) is one of the masterpieces of Persian Sufi literature, composed by the poet and mystic Farid al‑Din Attar of Nishapur in the late 12th or early 13th century. Written in rhyming couplets (mathnawi), it weaves together allegory, spiritual instruction, and poetic beauty to explore the journey of the soul toward divine truth.

The Allegorical Journey

The poem begins when all the birds of the world gather to discuss their troubled state. They have no king to unite them. The wise and eloquent hoopoe bird proposes that they undertake a journey to seek the Simorgh, the legendary king of birds who dwells beyond the mountains of Qaf.

But this journey is not an ordinary one. In Sufi symbolism, it represents the seeker’s spiritual path toward union with the Divine. The Simorgh is a metaphor for ultimate truth — God, or the perfected self — while the various birds personify different human failings, attachments, and virtues.

The Seven Valleys

The hoopoe explains that to reach the Simorgh, they must pass through seven valleys, each corresponding to a stage of mystical development:

The Valley of Quest – The seeker renounces comfort and security to begin the search for truth.

The Valley of Love – Love strips away reason, replacing intellect with passion for the divine.

The Valley of Gnosis (Understanding) – Deeper awareness dawns; the seeker begins to see reality as it truly is.

The Valley of Detachment – All worldly attachments, including self‑interest, must be abandoned.

The Valley of Unity – The seeker perceives the oneness of all existence.

The Valley of Bewilderment – Overwhelmed by the vastness of truth, the seeker is plunged into a state beyond rational comprehension.

The Valley of Poverty and Annihilation – The ego is extinguished, and only the Divine remains.

Each valley poses trials that test the birds’ resolve. Many turn back; others perish along the way.

The Arrival and Revelation

In the end, only thirty birds survive the journey. Exhausted, they reach the court of the Simorgh — only to find no external ruler awaiting them. Instead, they see their own reflection in a radiant mirror.

Here Attar reveals the central pun and insight of the poem: in Persian, Simorgh (سیمرغ) literally means “thirty birds” (si = thirty, morgh = bird). The seekers and the sought are one and the same. The Simorgh they longed for was never separate from themselves; their journey was the transformation necessary to perceive this truth.

Sufi Meaning

The Conference of the Birds is not merely a fable; it is a manual of spiritual awakening. The birds’ journey symbolizes the purification of the soul, the stripping away of illusions, and the realisation that the Divine is not an external entity to be reached, but the very essence of one’s own being. In Sufi thought, this is the stage of fanāʾ — the annihilation of the self in God — followed by baqāʾ, the subsistence in divine presence.

Cultural Legacy

For over eight centuries, Attar’s masterpiece has inspired poets, mystics, and artists worldwide. Its imagery of flight, longing, and self‑discovery transcends religious and cultural boundaries. The Simorgh, as both mythical bird and spiritual archetype, has remained a potent symbol in Persian art and literature, often intertwined with the myth of the Phoenix — another emblem of death, renewal, and eternal life.